My friend Dave once got brought in to help with a large project. The company was purchasing a large fax system from a vendor and then planned to extensively customize it to work in their environment.

As is his habit, Dave started asking questions about who the customers were, and why they wanted this fax system. He wanted to understand not just the specific details of what he was asked to do, but more importantly what problem they were trying to solve, and who they were solving it for. Everyone was focused on just their part and so it took some time to figure out the big picture.

Eventually he discovered that one person in the building was unable or unwilling to walk up two flights of stairs to get the daily faxes, and that had somehow escalated into this massive project.

So Dave walked upstairs, picked up the fax machine and physically moved it down to their desk, completely eliminating the need for a multi-million dollar project.

At this point you must be thinking that is so insane that I must have made this story up. Except that I didn’t, it really happened.

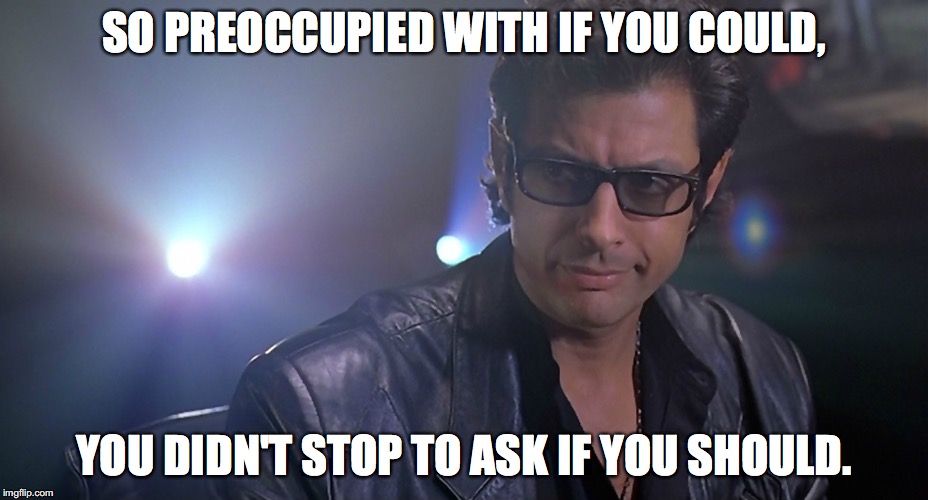

The question is why Dave was the only person in a long line of people who had actually looked at the real need. Probably dozens of people had been involved in discussions and planning around this project. Why had nobody else moved the fax machine?

I don’t know the real reason, but I can speculate. It’s likely that when someone first identified that there was a need to make faxes available, someone else saw an opportunity to do something that either made them look good or was intellectually challenging, and they chose to ignore the fact that it wasn’t really needed. Then as they added to that, they found more and more places that it could be used, whether or not those extra things were important to do. So the scope continued to grow and grow.

Before long, they were looking at a multi-million dollar project, with insignificant business value. Despite the lack of value, you can be sure that someone was going to get credit for delivering this large project though.

Then we couple that with the tendency of people to focus purely on the parts that they are personally responsible for, rather than the larger picture. In some cases, that’s because we’ve deferred to some expert that we assume already did the due diligence, and sometimes its because we just don’t want to.

I worked with one guy who strongly argued with me that he shouldn’t have to update XML files because he was hired to write Java, and another who wouldn’t update a ticket in Jira unless their formal job description explicitly stated that they had to. Some people develop tunnel vision and don’t want to focus on anything other than their own part.

Clearly, this project never should have got off the ground but once it did, other problems appeared.

Commitment bias, also known as the escalation of commitment, describes our tendency to remain committed to our past behaviors, particularly those exhibited publicly, even if they do not have desirable outcomes. … Someone experiencing commitment bias might think “I need to stick with this decision because backing out now would be highly embarrassing.” — The Decision Lab

The one thing I do know is that when the fax machine was moved and the project was cancelled, there were a number of people who were now very unhappy with Dave. They were embarrassed, now that their earlier decisions were under review, and it was obvious that this project never should have been funded.

Not a great outcome for Dave, as the work he’d been brought in for was now cancelled, however it was certainly the correct outcome for the company. They could now refocus on things that actually were important.

There are multiple lessons we can take from this:

- Sometimes we just need to pick up the fax machine. Look for the simple solution, and that means looking at the bigger picture, not just the piece we were asked to do. Anybody can create something complex but it often takes real experience to make something simple.

- The more committed we are in a direction, the harder it will be to admit, even to ourselves, that it was a mistake. Commitment bias and the related Sunk Cost Fallacy are very real. The earlier we can make the right go/no-go decision, the easier it will be.

- It often takes real courage to step up and call out the problems. Building an environment of psychological safety will reduce the amount of courage required, but not eliminate it completely. We still need people like Dave, who are willing to say those things that are hard to say.